You Are What You Say

Understanding and Describing Your Verbal Identity

When it comes to brand identities, the visual components, like logos, colors and photos, get most of the attention. That makes sense. About 30 percent of the human cortex is devoted to visual processing, as compared with 8 percent for touch and just 3 percent for hearing. The human brain processes images 60,000 time faster than text, and 90 percent of information transmitted to the brain is visual. The eye itself is considered an outgrowth of the brain.

But how we recognize, feel about and relate to brands is based on more than looks. The brand’s verbal identity — what the organization says and how it says it — matters, too. If the visual and the verbal aren’t in sync, the effect can be anywhere from comical to catastrophic.

What’s a Verbal Identity?

Here’s a good enough definition of verbal identity, but when it comes to creating and/or managing one, I think it can help to break it down into these four components: voice, tone, style and message.

| Voice: The overarching personality of your brand expressed through words in any content or communication you produce. | Tone: The particular mood and feeling expressed through words in a particular communication or piece of content. |

| Style: Choices regarding writing and speaking conventions, including sentence construction, usage, grammar, punctuation, spelling, capitalization and pronunciation. | Message: The information, idea and/or emotion the communication or content is trying to impart to the audience. |

Voice vs. Tone

Let’s take a moment to distinguish “voice” from “tone” because they are often used together (voice and tone, or tone of voice) and sometimes they’re used interchangeably, but they are not the same. Basically, your voice should be consistent, but your tone should change based on the circumstances.

Voice signals identity; tone signals mood.

You can identify who’s speaking by their voice. You can tell how they feel — or want you to feel — by their tone.

Your mom might have scolded you by saying, “Don’t take that tone with me!” But she probably never said, “Don’t take that voice with me!”

Voice is consistent; tone is contingent.

Changing or disguising your voice from one situation to the next could make you seem shifty or unbalanced. But, not changing your tone to suit the context or channel could make you sound robotic, uncaring or oblivious.

There are many voices; there are few distinguishable tones.

Each person’s voice is unique — at least as far we know. So, theoretically, each organization can have a unique voice as well.

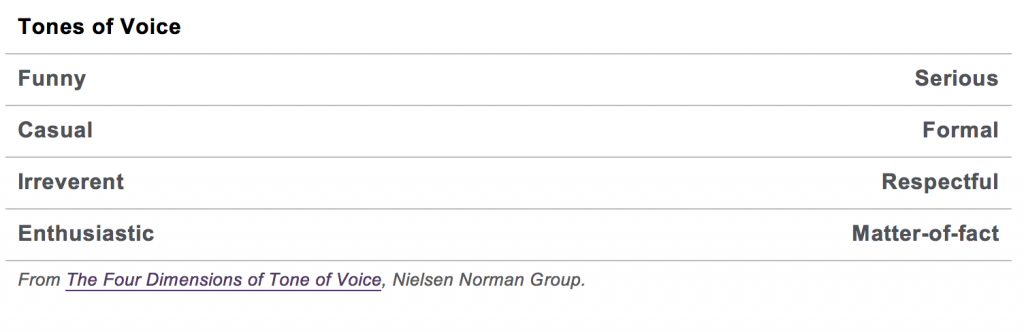

Tone is more limited. According to work done by Nielsen Norman Group, there are only four distinguishable dimensions of tone:

- Funny vs. Serious

- Casual vs. Formal

- Irreverent vs. Respectful

- Enthusiastic vs. Matter-of-fact

Here’s a Quick Way to Tell Voice and Tone Apart

Let’s say you’re communicating an increase in your company’s 401(k) match. Imagine how you might approach it …

… Oh, wait. Scratch that. The match isn’t increasing, it’s actually being eliminated.

The things that would change from one scenario to the next are your message and tone. The things about the communication that wouldn’t change are probably part of your voice and style.

How to Describe a Verbal Identity

Every brand guidelines document I’ve ever seen addresses visual identity, but not every one addresses verbal identity. And, those that do typically don’t do it with the same consistency and precision used to specify the visual.

This is understandable. Not only do visuals dominate our perceptions, but fundamental elements of a visual identity can be described with scientific precision. Colors can be specified by code numbers. Layouts can be defined by grids and measurements to the fraction of an inch.

In comparison (and quite ironically) verbal identities can be hard to describe in words. There’s no equivalent of a Pantone number that identifies a word or phrase as being within the brand’s voice palette. That and, since just about everyone has a pen and a keyboard, just about everyone thinks that they can write well enough without much guidance.

Where graphic designers are given measurements, codes, files and photos to work with, writers typically get a handful of descriptors, like “conversational,” “smart,” “trustworthy,” and “respectful.”

While HR is responsible for a great deal of content and communication that contributes to the overall employee experience, it usually does not own the organization’s brand identity. But, HR can and should maintain its own style guide as a subset of the organization’s brand guidelines.

Based on a review of the many brand guidelines documents we’ve gathered over the years, here are a few tips for creating a useful set of verbal identity guidelines. (The following assumes that your organization’s voice is described, at least to some degree, in its overall brand.)

1. Identify common categories of content and communications.

Focus on categories that make a difference, on those that might trigger a different tone. For example, do you communicate differently to recruits than you do to retirees or to the executive committee? Is there anything different about how you communicate about performance management than about your health and welfare benefits?

2. Provide examples.

Alone, a few descriptive words or phrases don’t offer a writer much guidance. For example, one of the most common verbal identity descriptors I come across is “conversational.” A conversational tone among physicists is probably different from a conversational tone among web designers. Craft a few “do” and “don’t” paragraphs to clarify what you’re going for in each category.

3. Describe your tone(s) on a spectrum.

As mentioned above, there are only so many distinguishable tones. You could spend hours combing through a thesaurus looking for the right descriptors, but is a writer going to know how to sound “progressive”? When describing your tone(s), try to confine yourself to the four dimensions below and plot each dimension on a spectrum. For example, “funny vs. serious” could be anything from “laugh out loud” to “pleasant” to “straight-faced”. Even with this more focused approach, there is still a great deal of variety and flexibility. But, be sure the tones you describe are compatible with your overall voice. I recall one of my high-school English teachers, a Jesuit priest who described himself as a “loveable curmudgeon.” His idea of being “funny” was reading a passage from To His Coy Mistress and then muttering that he “lived vicariously through literature.” It was funny in his voice, but it probably wouldn’t be funny in Amy Schumer’s.

From The Four Dimensions of Tone of Voice, Nielsen Norman Group.

4. Have some style.

If your organization’s brand standards don’t identify a style guide (e.g. Associated Press or Chicago Manual of Style), pick one. Also, make a list of your benefits, programs and key terms to confirm spellings and capitalizations. Is it medical plan or Medical Plan? Is it pretax or pre-tax?

5. Nail down some core messages.

Over time, identify and catalog certain core messages and descriptors that really nail your voice and clearly communicate your intent. Think about it. How many different ways does Geico say “15 minutes could save you 15% or more on car insurance”? There’s very little, if any, variation. Consistent messaging and disciplined repetition can build recognition, accelerate understanding and burn your messages into memory.

Let’s Connect

Are you working on your organization’s or department’s verbal identity? Share your story with us. If you’d like some help, we’d love to hear your voice — no matter what tone you use.